Because You Demanded It

How Bridget Christie found the funny side of Brexit

After the EU referendum result, Bridget Christie ripped up her Edinburgh show and created a new one in just a few weeks. This is an anatomy of a standup set that has changed with the headlines

Written by Ben Williams in The Guardian on February 3rd, 2017

‘I never don’t write’ … Bridget Christie in her home office. Photograph: Martin Godwin for the Guardian

Creating a new hour of standup can be a lengthy process. Most comics spend months writing material and honing punchlines. For many, performing a run in Edinburgh is the final goal. For more established names, there’s life after the fringe, with possible London runs and national tours. So what happens when, after months of labouring over an idea, world events derail your plans? On 23 June, Britain voted to leave the EU. Suddenly that seemed far more important to Bridget Christie than the topic she was writing about, so she ripped up her show and started from scratch.

I meet Christie in a cafe near her home in Stoke Newington, north London, to talk through the creation of that new show – how every idea was formed, every punchline introduced, all in just a matter of weeks. She sits down, opens her rucksack and pulls out reams of A4 paper – drafts, handwritten set lists and pen-marked notes like handed-back school tests. So let’s start at the beginning.

9 February 2016

It’s deadline day for comedians to submit information about their show for the Edinburgh fringe brochure. The festival doesn’t start until August so many comics will start by picking an ambiguous title and then flesh it out into an hour of standup nearer the time. But Christie has already decided on the theme for her next solo show. Mortal will be its title, and death and mortality will be the big topics.

Since 2008’s A Ant – in which Christie used ants as a metaphor for female comedians – the Gloucester-born comic has explored gender politics in increasing depth, including the Edinburgh Comedy award-winning A Bic for Her in 2013. This year, she decides she wants to talk about something more universal. “We all die, it’s something we all have to face,” she says. “I thought: surely there must be a way of making it funny?”

Christie became fascinated with death after reading Being Mortal by the surgeon and writer Atul Gawande. The book explores modern medicine’s ability to prolong life while looking at how we confront mortality and care for the elderly and terminally ill. “It’s one of the best books I’ve ever read,” she says

4 April

The EU referendum is two months away, and the key campaigning figures and their tactics are dominating the headlines. With the latest polls showing a gain for leave, Christie begins to worry. She’s sitting in her kitchen thinking about Mortal, and looks out at her garden. “I love gardening so much,” she says, “and I particularly adore my fuchsia. I thought: I don’t know if I really want to keep thinking and talking about feminism, politics and death. I might just do a nice show about gardening.”

23 May

Christie is performing a 30-minute Edinburgh preview in London at the Leicester Square theatre’s basement studio to an audience of 60. She has one page of written material that lasts about 10 minutes and the rest is improvised. Her method for testing jokes will be familiar to many comics: she marks a tick next to each gag that gets a laugh and a cross next to one that doesn’t, all while she’s on stage.

Tonight, she kicks off the gig with an announcement: she’s dying. “Don’t let that affect the way you respond to the show,” she tells the audience. “Don’t laugh out of pity, just because I’m dying. Only laugh if you think I’m funny. Oh yes, when I say I’m dying, I don’t know when, or how, but I will definitely die at some point, probably somewhere towards the end of my life. All of us in this room will. We will all be dead. Anyway …”

The show doesn’t go too well (I count five ticks) and her son’s best friend’s mum was in. “I thought that was a funny opening line,” says Christie, looking back, “but people just didn’t like it. With standup, if you just talk on stage, your clearest ideas come out. But that’s just the idea,” she stresses. “Then you have to make it funny.”

She writes constantly, whether at home on a computer or jotting down ideas while out and about. “I never don’t write,” is how she puts it. Different sections require different writing techniques, though. “Some things in a show need to be precisely written,” she explains, “so that the point you’re making is clear. Other things can be more conversational. But it all needs to sound like spoken word, not written.”

Christie opens her shows fairly loosely, with a few comments that change each night depending on the venue and audience. But then she sets up the idea for the show and stays more on script. There’s a particular structure and pace to a Christie show. After writing 11 solo hours in as many years, she can get a sense of the show’s shape by looking at it on the page, she tells me. “Everyone works differently and my technique may sound anal and nerdy, but if I laid every page out on the floor, it should look a bit like this: lots of short paragraphs for about four or five pages, then a big bit – which is a stream-of-consciousness thought with no punctuation or sentences – and then more shorter bits towards the end. Some years you don’t find that ‘going off on a tangent’ bit and it always feels like there’s something missing.”

1 June

It’s half-term, and Christie is visiting her dad in Gloucester. While talking about the possible referendum outcomes he tells his daughter a story about her mother, who also loved gardening and, like her daughter, was particularly fond of fuchsias. Christie’s Irish mum brought back some soil from her parents’ farm in Ireland, mixed it with the British soil in her garden and grew a fuchsia. It’s a story Christie found very moving. “I thought there might be something in that, for the end of the show.”

24 June

The morning after the Brexit vote. The results are in. It’s a shock to many, including Christie. Tonight, she’s meant to be talking about death at London’s Soho theatre. But that now seems irrelevant.

“I felt that I couldn’t go out to central London and not talk about what had happened,” she explains. So she types up her Brexit feelings and reads them out on stage that night. “Today is a dark day,” she tells the audience, before examining how Nigel Farage fooled half the UK, comparing him to the blue and black or white and gold dress meme. She expresses her shock and upset at the murder of Jo Cox, and the little impact it had on the polls. She mocks Michael Gove’s comment that people have “had enough of experts”, and his shunning of economists, joking that he must hate numbers so much he probably just takes random amounts of antibiotics rather than the prescribed amount: “Take one four times a day? Says who? Some unelected Brussels bureaucrat? I’ve had enough of numbers. I’ll take as many as I like.”

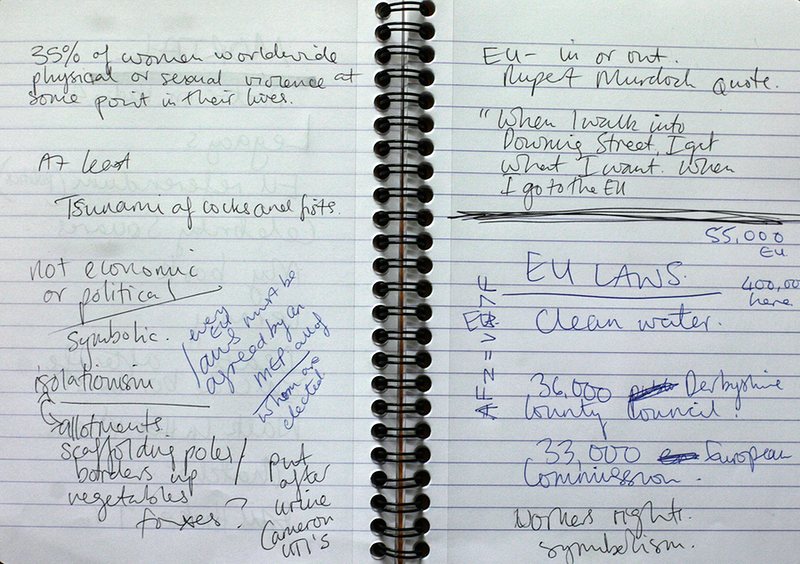

Bridget Christie’s notes for Because You Demanded It. Photograph: Martin Godwin for the Guardian

Over the next few days, Christie puts Mortal aside and uses her hastily written thoughts as a starting point for a new post-referendum show entitled Because You Demanded It. Looking back on the notes she wrote that day, it’s incredible to see how many of those ideas ended up in the final show. Sometimes anger feeds creativity.

“Death was no longer important,” says Christie. “I thought I should talk about such a seismic political event and, anyway, it’s good to take a risk sometimes. What’s the worst that can happen? You get loads of two-star reviews, no one comes and you lose your income for that year …”

27 June

Racing to keep up with referendum repercussions, a BBC reporter interviews a leave voter with a swastika tattoo on his arm, and Christie can’t believe he’s not challenged on it. “I watched it go out live and seem to remember EU fishing quotas being mentioned as one of the reasons the man voted leave,” she recalls, “unless I dreamed that bit. I thought I might be able to do something linking neo-Nazi symbolism and the Icelandic mackerel dispute.”

In the final show, the story of this vox pop is broken up into several sections as Christie uses it to detour into other topics and tangential thoughts, all the while returning to the unchallenged racism. “I wanted to talk about media coverage, and how I felt the BBC’s political editors were failing us by not calling out fascism for what it was, but presenting it as a legitimate part of the debate. Then focus on society, and ask: where do you even get a swastika tattoo? Are there specialist white supremacist tattoo parlours or do tattoo artists have the equivalent of the Hippocratic oath? Then eventually it’s about the big conversation: how did we get here?”

Over time, the BBC interview becomes one of the backbones of the show, and it provides a neat (and memorable) callback at its conclusion, when Christie takes off her jacket to reveal her arms are covered in felt-tip pen swastikas … and one fish. “Really, the man interviewed wasn’t covered in swastika tattoos, he just had one, but I don’t think we need to worry about exact numbers in the current climate, do we? Numbers are just for economists to patronise the working classes with. And anyway, I think we’d all agree that any more than none swastika tattoos is too many swastika tattoos.”

7 July

Christie is previewing the show at London’s Always Be Comedy alongside her friend and fellow comedian Nish Kumar. They discuss post-Brexit Britain and the rise in race hate crimes since the result – something Kumar has experienced. On the night after the vote, as he was on stage at the Comedy Store, a heckler told him to “go home”. Kumar encourages Christie to pursue an idea she has about racism and the demonisation of the white working class. The show’s coming together at a rapid pace.

9 July

Christie’s newsletter announces that she’s scrapped Mortal and will be doing a new show on Brexit instead. But right now, she’s got other things on her mind. Today, she’s going on holiday with her family.

“We go to the same place in France every year, at the same time – after school breaks up and before the fringe” she explains. “It’s where I finished my last three shows. But this year, I forgot about the show. I felt like I needed to clear my mind.”

When she returns to the UK, a week before the festival begins, she has about 30 minutes of material, so books in some emergency previews. Her friend, writer and actor Brona C Titley, comes along and they look at the show’s structure together.

2 August

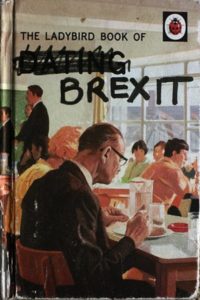

Christie’s Ladybird Book of Brexit, featured in her show. Photograph: Martin Godwin for the Guardian

After frantic rewriting, Christie’s performing a last-minute preview at the Museum of Comedy in London. Many of the show’s big themes are taking shape, but she’s struggling to figure out exactly the significance of her mum’s fuchsia, and how that relates to Brexit.

“I couldn’t quite put my finger on it,” she says. “I called Alison Vernon Smith, who produces my radio shows and who is really great at telling me what I mean about things, and we got to the bottom of it.”

In a new gardening/Brexit metaphor, immigrants become plants and the UK becomes soil, and from that sprout more gardening-related metaphors about patriotism and the positives of mixing cultures with ours. “It really was lucky that fuchsias were not indigenous to Britain,” she says.

5 August

It’s 11am, and the venue in Edinburgh is sold out for Christie’s first show. It’s the time slot-venue combo that’s become Christie’s fringe trademark. “I can’t imagine where else I’d play in Edinburgh now,” she says. “The Stand is a club all year round, so it has a great lived-in atmosphere. It’s the perfect room for standup: low ceilings, a small stage and cabaret-style seating at the front.”

During previews audiences have, largely, been split on Brexit. So how does a firm remainer get her opinions across without alienating up to 52% of her punters? It’s about finding the common ground, she says. “Lies were told and promises broken. I don’t think anyone got what they wanted.”

Christie thinks about her new fuchsia-metaphor ending and the subject she really wanted to write a show about – her garden – and she has an idea. “I thought, I should be trying to do a show about gardening, but whenever I try to talk about my garden, I get distracted.” The show’s opening takes shape. She jokingly gives the audience the option to leave if Brexit does distract her, and her show becomes a referendum in itself.

11 August

It’s more than a week into the festival, and almost two months after the vote. The focus of Brexit is shifting from the dividing campaigns to the terms of our exit, and Christie is determined not to let people forget. “Johnson and Gove behaved like childish twats,” she says. “It was all just a game to them, to further their own careers. It’s really important to remember that.”

Christie writes her own “Ladybird Book of Brexit” to read at the end of her show – all the lies and motives and backstabbing – in blunt, simple detail. Add to that the Irish soil story and her tattooed arms, and it’s a powerful finale, and elegantly sums up the anger and absurdity of post-Brexit Britain.

29 August

It’s the last day of the festival and Christie’s final performance. Over the month, the show has changed by about 25%, she reckons, as she workshopped ideas, honed her thoughts and kept up with the news.

The death show isn’t totally dead – she plans to return to the idea at some point – and the odd joke has slipped into the Brexit show, reshaped to fit the narrative. There was a section in Mortal where Christie explained that she wouldn’t lie to her children about death, which she subtly reworked. “I linked it to not lying to them about politics or religion either,” she explains. “It was much longer in Mortal, but I cut it down and used it to connect a routine to my Ladybird Book of Brexit, which I say I wrote for my children.”

Largely, though, she has written a new hour of comedy in just a few weeks, and it’s a risk that’s paid off. Because You Demanded It is bold, brave, passionate and playfully absurd.

The sheer topicality of the show is impressive. Many comics touched on Brexit during the festival. But Christie really took ownership of the topic, and it was her furious bafflement at the situation that made her show so funny. Her exasperation was genuine and affecting.

Critics agreed. Because You Demanded It became one of the most acclaimed shows at the festival, racking up eight five-star reviews. “I didn’t used to read my reviews until I got back from Edinburgh,” says Christie. “I do now, though, only because I’ve done 11 shows in a row, so I’m calmer about them.”

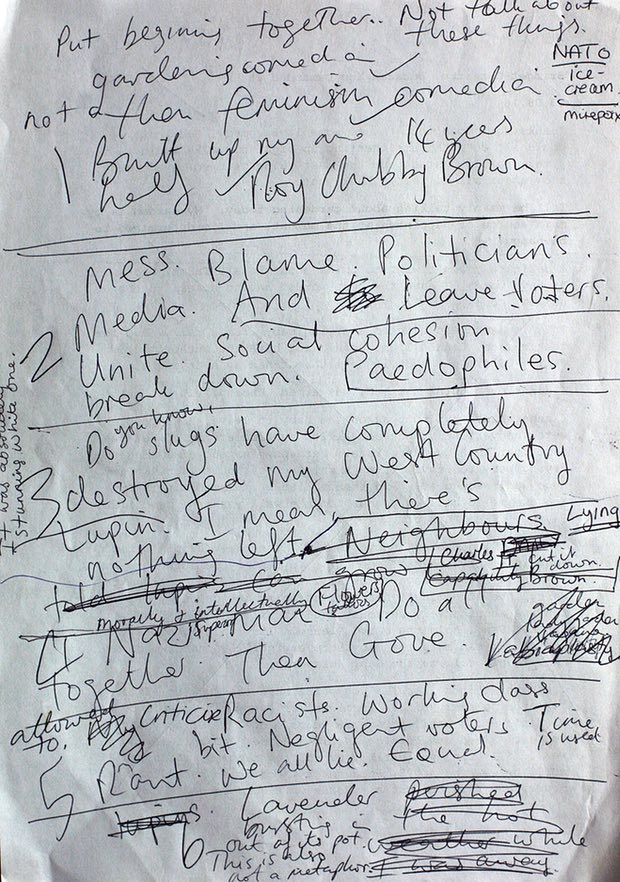

‘My job is to make politics absurd. I’m becoming increasingly irrelevant’ … Christie’s notes. Photograph: Martin Godwin for the Guardian

29 September

It’s a month since the fringe ended, and Christie’s been busy reworking her show. Ahead of a national tour next year, she’s performing Because You Demanded It twice a month in London, so that she can update the material as events unfold.

Tonight’s show at the Leicester Square theatre includes new gags about Jeremy Corbyn, Labour and, with the US election edging closer, Trump. “This man ejected a crying baby from a rally,” she says on stage. “And for that reason, Donald Trump should not have the authority to deploy US troops. Not if he’s threatened by a crying baby. I don’t even think the baby was armed, unusually.”

Everything is always a work in progress, says Christie. “I don’t think there’s a writer alive who thinks whatever they’ve done is the best it could possibly be. There is no end point.”

22 November

After two shows in September and two in October, Christie’s back in Leicester Square. I haven’t seen the show since Edinburgh, and it’s fascinating to give it a second viewing and see how it’s progressed.

Tonight there are new sections on Marine Le Pen, Gina Miller’s legal challenge, and “men of the people” Farage and (now victorious) Trump taking a photo in a gold-plated lift. “My job is to make politics absurd,” says Christie to the 400-strong audience. “I’m becoming increasingly irrelevant.”

24 January 2017

Christie’s two-week London run starts in a week, and there’s been so much news over the last two months that the show is being reshaped yet again. Trump’s inauguration and his “alternative facts” about the crowd size, the supreme court ruling on Article 50 and Theresa May’s Brexit speech will all potentially be included. “She confirmed we’ll be leaving the single market in order to control immigration and our borders,” explains Christie. “But everyone knew that already. It was only her that thought she could do both. No one else did. It was like a speech for herself, really.”

Seven months after the vote, it’s obvious that Christie’s anger about the referendum hasn’t dampened. If anything, she’s more furious than ever. As time has passed, the actions of Johnson, Gove, Cameron and Farage seem increasingly ludicrous, and Christie’s determined not to let us forget how we ended up in this mess of uncertainty. “It’s important people remember the details,” she says. “We have to remember why we’re here and how irresponsible everybody was.”

After performing the show in remain-voting London, Because You Demanded It is going on a national tour, to all corners of this divided nation. “It will certainly be an eye opener,” admits Christie, “and it will be interesting, for me, to see how the country responds to it. We’ll see, won’t we? And then that will be another story.”

Bridget Christie: Because You Demanded It is at Leicester Square theatre, London, until 11 February and then on tour.

Written by Ben Williams in The Guardian on 3rd February 2017.

Filed Under: Because You Demanded It, Feature